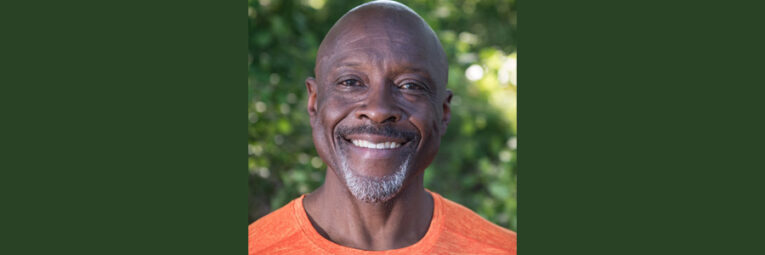

Anthony Taylor knows that nature is fundamental to our experience as humans, and they are on a mission to ensure that all people reap the benefits. For Taylor, their journey began “selfishly,” or so they say. They laugh and continue, “I no longer wanted to be the only Black person on my bicycle rides.”

Bicycling has been a lifelong passion for Taylor, who spent much of their young adult life training and enjoying rigorous, multi-day, cross-country bicycle trips. It’s also a sport with few black participants.

One day Taylor was in the basement of a Minneapolis bicycle shop when they came upon a book. On the cover was a black-and-white photo of the world’s fastest bicycle rider—a Black man named Major Taylor (no relation to Anthony).

Regrettably, history has largely forgotten Major Taylor who, despite enduring racism that barred him from races, turned him away from restaurants and hotels, and ridiculed him with racist insults, went on to earn world champion titles and become one of the highest-paid athletes in the late 1800s.

Anthony Taylor was astonished and inspired. Collaborating with friends, including Louis Moore, they founded the Major Taylor’s Bicycle Club of Minnesota in 1999. One of the club’s first endeavors was to provide training assistance to three Black women who participated in the 500-mile AIDS Ride. Since then, the club has grown and become part of a national movement of Black-led bicycling clubs.

This would become Taylor’s life work—creating opportunities for underrepresented communities to get outdoors. But that wasn’t apparent from the start. Fresh out of college in 1982 with a degree in chemical engineering, Taylor spent four years in that field before moving into a job managing fitness centers. One thing led to another—including earning two Executive MBAs along the way—until eventually, Taylor began working for nonprofits like the Loppet Foundation and the YMCA of the North and the Cultural Wellness Center. Here they led efforts to build equitable access to the outdoors year-round.